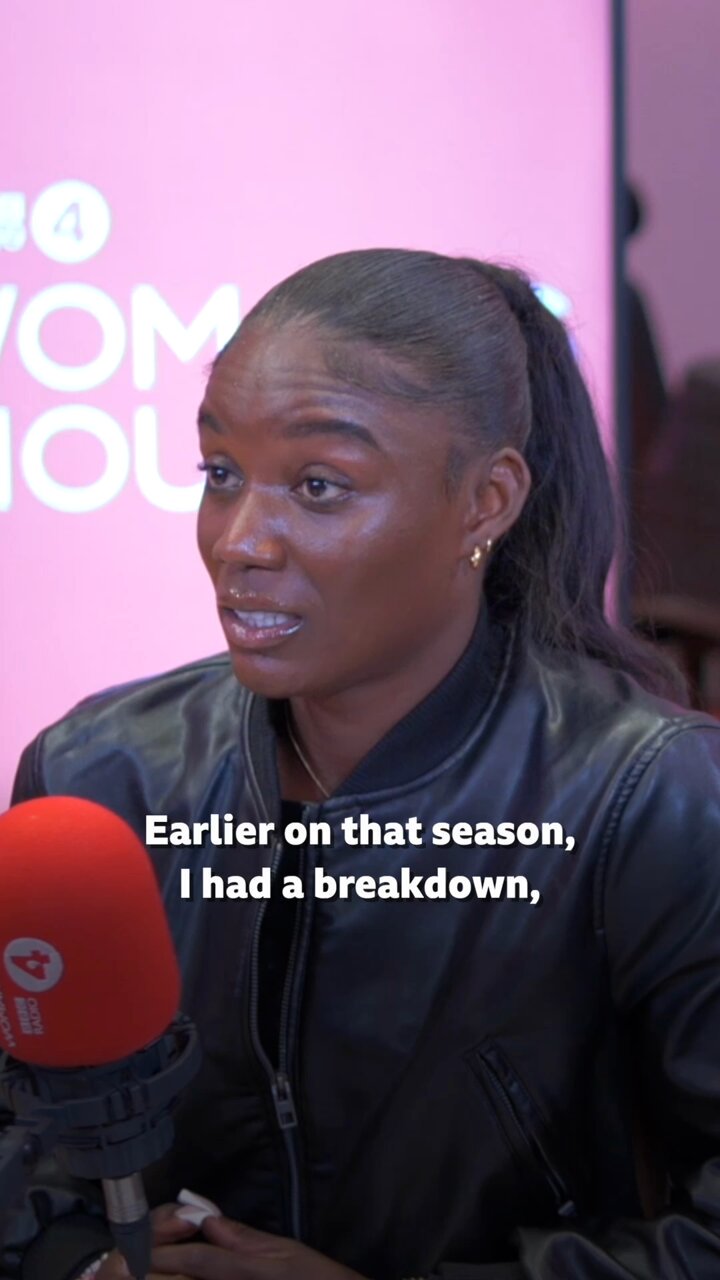

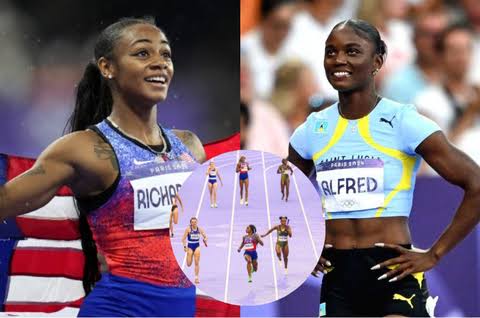

Alfred was an outsider and a relative unknown when she stood on the starting blocks on the purple track in the pouring rain at the Stade de France on August 3. Sha’Carri Richardson had won gold at the World Championships the year before and was the favourite, while no one from St Lucia had ever won an Olympic medal of any colour. Just 10.72 seconds later, the Caribbean island had a new hero and Alfred’s life changed completely.

“Crazy” is the word the 23-year-old uses to describe the period since Paris. She is speaking to Telegraph Sport after arriving in London on a flight from a post-Olympic awards event in Portugal and adds: “[It’s been a] whirlwind for sure, but I have felt a lot of love and support from a lot of people over the past few months, from St Lucia, from around the world, from Caribbean people… overall, it’s been a great feeling.”

St Lucia has a population of fewer than 200,000 and first participated in the Olympics in 1996 in Atlanta. Despite sending athletes in disciplines from athletics, swimming and sailing, the nation had not seen anyone stand on the podium until Alfred.

Little wonder the small Caribbean nation has gone all out to celebrate Alfred’s achievements (she also won silver in the 200m). That has included a national Julien Alfred Day on September 27, when a capacity crowd attended a free concert at the Daren Sammy Cricket Ground, a stadium named after another famous sporting St Lucian.

A section of the Millennium Highway has been renamed the Julien Alfred Highway; she received a million-dollar award from the government, as well as a 10,720 feet area of land, in commemoration of her winning time. Alfred’s face will also feature in a series of exercise books and there will be a stamp designed in commemoration.

When asked if her life now is different to that before Paris, the answer is straightforward: “Definitely. I get recognised more in person and wherever I travel. Even my family members. Now people know they’re my brothers and sisters, they get recognised as well and they get approached in town, at work, so it’s been life-changing for them as well.”

Alfred’s athletics journey began at primary school. She recalls racing for her colour house at Ciceron RC Combined School in Castries, the St Lucian capital: “Running against the young girls, and even boys at times, when it got really competitive at my primary school – I think that was my first memory of sprinting.”

Her life could have taken a vastly different direction without a couple of key interventions, though. Alfred’s talent was recognised not by an athletics coach but by school librarian Brenda Virgil. She introduced Alfred to coach Cuthbert Modeste (also known as Twa Ti Ne) and from the age of nine training became more regimented for the next three years.

However, after losing her father at the age of 12, Alfred took a break from sprinting and then stopped participating in the sport completely. She only returned to the track because of her childhood coach; Modeste went looking for her in the Ciceron community and encouraged her to return to sprinting.

His powers of persuasion paid off a decade later when Alfred won that Olympic final and it was her father who she thought of in Paris. “I’m thinking of God, and of my dad, who didn’t get to see me,” she said in her post-race press conference, with gold medal secured. “Dad, this is for you. I miss you. I did it for him, I did it for my coach, and God.”

‘Usain Bolt was my idol’

Preparing for a final is something all athletes do differently. Some prefer quiet contemplation, others are loud, trying to psych out other opponents or pump themselves up. For Alfred, she went back to her idol Bolt and revisited some of his top moments to visualise her own.

“In grade six, we were asked what we wanted to be when we grew up and I said ‘the female Usain Bolt’,” Alfred explains. “It’s very cringe saying it now, but I wanted to be just like him.

“I grew up watching him, watching all his races. We didn’t have any St Lucians in the race, so I was always wanting him to win, I wanted Usain Bolt to win, he was my idol. I looked up to him.”

It is a part of her life that came full circle when she sat in the Olympic Village in Paris: “Even before the Olympics, I had to go back to that inner child and just look at how great he was and picture myself being just like him, so I really had to do that the morning of my race, the finals day.

“Before the day of the finals I had been doing a lot of visualisations with my coach. So I think in that moment when I woke up, I just wanted to take it to a different level and picture myself crossing the line and just celebrating and being as good as he was.”

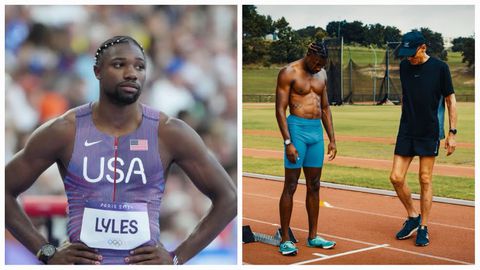

Alfred may be inspired by Bolt, but she has taken a different approach to the limelight. Bolt was known for his trademark celebrations, expansive brand endorsements and fun-loving personality. Other sprinters like the United States’ Richardson and Noah Lyles are also known as extroverts and have attracted a global audience to the sport, with their followers on Instagram in the multi-millions.

However, Alfred confesses she is “not too fond of social media”, despite her own following growing from a modest 30,000 before the Olympics to 154,000 ahead of Netflix’s Sprint 2. Although she features in the second series of the documentary, Alfred also remains unsure whether she will watch it, admitting: “I’m not the type of person to listen to myself, when I’m on TV or YouTube, because hearing my voice makes me cringe. A lot.”

It is clear that the sport itself is Alfred’s passion. She cuts a relaxed figure away from the track, smiling and laughing during Telegraph Sport’s photoshoot as she prepares for a week in London, but once she is on that start line there is a steely focus.

“It’s almost like an alter ego,” she says. “Sometimes I can be just regular, having a little chit-chat like we are now, or a little laugh with somebody and just talking so calmly. But when I’m on the track I don’t talk. I don’t have any friends.

“I don’t care who you are or how good our friendship is outside of track and field, it’s just a whole different mindset and I’m just hungry.”

‘I had to adapt to not being with any family’

It is that hunger that has driven Alfred’s career and saw her move overseas twice before she turned 18.

At 14, Alfred left friends and family behind to harness her sprinting ability in Jamaica. She becomes slightly emotional recalling how hard it was to leave home when “very young”, saying: “First of all just not being with any family. That was something I had to adapt to. I don’t think I fully adapted to being away from my family for the three years that I spent there.

“But the culture difference, the language, the environment of what sport was like, what sprinting was like and what track and field in general was like in St Lucia, compared to Jamaica, is completely different.”

It was Jamaica’s sporting prowess that made the decision worth it for Alfred, who says: “We hear about Elaine [Thompson-Herah], we hear about Shelly [-Ann Fraser-Pryce], we hear about Usain Bolt, so I think that was one of the reasons why I wanted to go to that environment, knowing that greats have come out of it.

“Being a kid you’re excited to go on an adventure at times, you’re just inquisitive. I think at that time it was just ‘I want to go to Jamaica’, so I wanted to take the opportunity, and I took it and made the best out of it.”

Three years later Alfred relocated again, this time to Texas to train under Edrick Floréal, a two-time Olympian from Canada. It was another challenging experience as Alfred moved into dorms alone, but she developed further as a sprinter in National Collegiate Athletic Association events.

“He’s somebody I felt was just meant to be part of my journey,” she has said of Floréal, who also coaches Britain’s Dina Asher-Smith. She credits the coach with helping her turn the pressure of having an entire country watching her into motivation to deliver.

That approach helped her to deliver St Lucia’s first medal at a global championships in March, winning gold in the world indoor 60m in Glasgow, before making yet more history at the Olympics.

“It still feels surreal to me to be honest,” Alfred says of the moment she realised she had won gold. She crossed the line with the eighth-fastest women’s 100m time in history and celebrated by pulling her bib off, holding it aloft to the camera and pointing to her name, but a few months on she is thinking of her next goals.

“Unless someone mentions it to me or it’s spoken about, I don’t really think about it. I think now I have almost moved on from it because I’m preparing for another season and there are World Championships coming up, so I’ve prepared myself not to get too comfortable now that I’ve won Olympic gold, but still realising how great I did in Paris.”

Regardless of what else she achieves, she has undoubtedly inspired a new generation of St Lucian sprinters, just as Bolt inspired her.

Leave a Reply